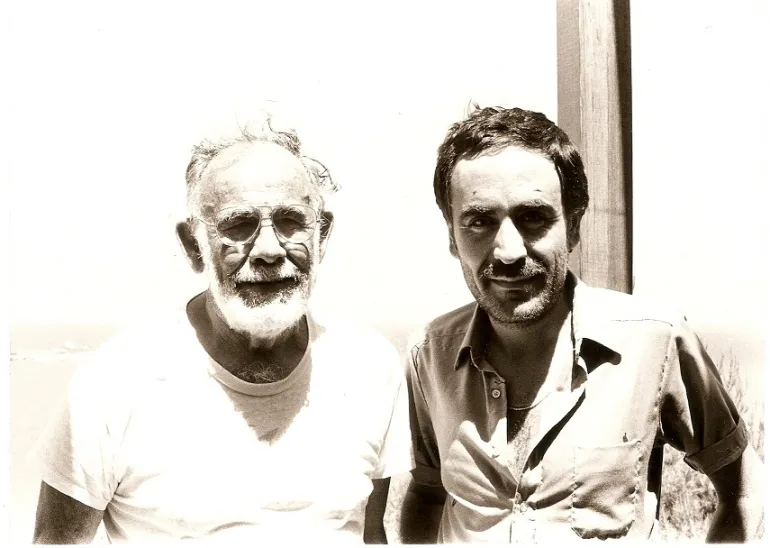

Η Ρενέ Πάπας Ελληνίδα που υπήρξε σύζυγος του μεγάλου παραγωγού Jerry Wexler έστειλε στον Πετρίδη το παρακάτω σημείωμα από το αρχείο της.

Η Ρενέ είχε γνωρίσει στον Γιάννη τον Wexler που είναι ο παραγωγός στα καλύτερα τραγούδια της Aretha και ουσιαστικά ο άνθρωπος που δημιούργησε την καριέρα της,

Ατέλειωτες οι συζητήσεις τους για την ιστορία της μουσικής στο σπίτι που έμεναν στην Ραφήνα.

Το σημείωμα είναι γραμμένο από τον Jerry Wexler που περιγράφει πώς την γνώρισε και την ιστορία πίσω από ηχογραφήσεις τους, και από τον βιογράφο της, πολύ γνωστό όνομα, τον David Ritz.

THE QUEEN

by JERRY WEXLER and DAVID RITZ

1966.

A different time, a different place, a different world.

Soul was the music of the moment. It might have been ancient as the Delta blues, but it was suddenly seen as new, fresh and hot.

At Atlantic Records, the crew had kept the faith. Ahmet, Neshui, Arif and myself had retained our fanatical passion for African American music. We had shepherded our sound from the nascent R&B of the fifties to what was shaping up as the black-and-proud sixties. We had survived the loss of our premier artist—Ray Charles—to ABC Paramount and were enjoying a strong run of hits with Otis Redding and Wilson Pickett. Sam and Dave were hitting on all cylinders and Percy Sledge had knocked it out of the ballpark with “When A Man Loves A Woman.” In the midst of the Motown phenomenon-- not to mention the Beatles, Byrds and Stones-- we were holding our own.

As a producer I was going through a born-again experience. No, it wasn’t the evangelicals who took me to the river; it was a bunch of bad-ass white boys from Muscle Shoals who converted my production methods from old school to new. Old school meant having arrangements written out beforehand. New school meant going with the spirit and making it up on the spot. I loved this approach of building ad-hoc head arrangements rooted in the rhythm section. It was daring, exciting and perfectly suited the sensibility of explosive singers like Pickett.

This enlightened—and looser—approach took me from the cold steel canyons of midtown Manhattan to the red clay soil of Alabama. I was a New York Jew living in temporary exile in the land of a thousand dances. The Muscle Shoals musical mensches—David Hood, Barry Beckett, Roger Hawkins, Jimmy Johnson, Dan Penn, Spooner Oldham, Eddie Hinton,

Donnie Fritts—had become my soul brothers. I couldn’t have been happier.

~~~~~

I was in the Muscle Shoals studio the day that the word came down about Aretha. It had been a rough afternoon. I was producing Pickett when he nearly came to blows with Percy Sledge. Seeing that two major Atlantic artists might be injured out of commission, I bravely stepped between the two. I nearly got my own head taken off, but somehow survived the ordeal. Pickett was back in the vocal booth when the phone rang.

Louise Bishop, a hip gospel deejay from Philly, was on the long-distance line. She said it succinctly.

“Aretha’s ready.”

I had had my ear tuned to Aretha for the past five years. Her preacher father, a friend to Dr. King and legendary civic leader in Detroit, had signed her to Columbia in the early sixties when she was still a teenager. That’s when my great friend John Hammond began to record her. Hammond knew jazz and blues as well anyone. The world remembers him as the A&R man behind Bessie Smith, Benny Goodman, Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. For all his acumen, though, John didn’t get Aretha exactly right. It wasn’t his fault. In fact, his first few Aretha records were wonderfully bluesy. But John’s superiors were looking for crossover hits. They wanted to turn Aretha into Diahann Carroll. Aretha can sing anything, and at Columbia she sang everything—and sang everything well. But the ambience didn’t suit her sacred style. She had no major commercial hits with Hammond.

Meanwhile, as Aretha herself wrote in her autobiography, From These Roots, “ I was vacillating between material for adults and songs for teens. John Hammond was out of the picture after the first couple of sessions. I never knew why.”

There was the added irony that, after leaving Detroit for New York and a contract with Columbia, world’s largest label, her childhood friends who had stayed home—Smokey Robinson and company—were hitting it big on Motown. Understandably, Aretha wanted to hit it big as well.

Minutes after Louise Bishop’s tip, I called Aretha and said it straight. “I’d love to have you on Atlantic. I’d be honored. Can we meet in New York?”

Agreed.

A week later, a lovely quiet-spoken woman walked into my office.

“Mr. Wexler,” she said, “I’m Aretha Franklin.”

She introduced me to the man who was then her husband, Ted White.

Without a lawyer, manager or agent, we made a handshake deal. That deal stood, without a day of conflict, for the next thirteen years.

Thus began the Golden Reign of the Queen of Soul.

~~~~~

Who was the woman who walked into my office four decades ago?

I have worked with a couple of geniuses. Ray Charles and Bob Dylan come to mind. In each case, the artist had a singular gift that turned the music world on its ear. In each case, the artist had a voice that spoke for millions. In each case, the artist projected feelings and ideas that crossed boundaries, continents and oceans. With all that in mind, I certainly consider Aretha a genius.

But this I must confess: When I signed Aretha, I knew her only to be a first-rate secular singer with righteous gospel roots. I knew she was capable of great things and, God willing, top ten hits. But there was no way of diving the forthcoming range and depth of artistry.

That’s why I initially offered her to Stax, the Otis Redding made-famous Memphis label we were distributing. I told Jim Stewart, Stax president, that if he covered Aretha’s $25,000 signing cost, he could turn her over to his producers while Atlantic handled promotion and distribution.

Jim passed.

Have mercy!

Let me be clear: I was not looking to shuck off Aretha. I knew she was wonderful. But the truth is that at the time I was overwhelmed with work.

Nonetheless, the responsibility was on me. I had signed her and I would produce her. I began cautiously. It wasn’t long ago, after all, that Ahmet and I had signed and failed with Mary Wells after she left Motown. Mary’s hits were so closely tied to the peculiarities of Smokey’s songs and Motown’s streamlined sound that we simply couldn’t duplicate that aesthetic.

Aretha was different for several reasons. First, unlike Mary, she had not yet enjoyed a series of major hits. Mary had established a style. Aretha had only suggested a style. That style required cultivation. But how?

Because she was already living in New York, I considered recording Aretha in the city. By now she was a sophisticated artist and New York had the country’s most sophisticated studios, not to mention superb musicians. New York made sense.

On second thought, though, Muscle Shoals made more sense. Muscle Shoals, like Aretha, was downhome and unpretentious. Muscle Shoals was closer to her musical roots. And the Muscle Shoals rhythm section had that deep-pocket groove.

At the center of my plan, of course, was Aretha herself. And not simply Aretha the singer, but Aretha the pianist. Putting Aretha at the piano was the linchpin of the strategy. Like Ray Charles and Donny Hathaway, Aretha was, is, and will always be a keyboard-based artist. Her relationship to that orchestral instrument is organic and absolutely essential to her expression. It’s who she is.

My idea, then, was simple: Let Aretha be Aretha. Let her be comfortable. Let her play piano. Let her help develop the rhythms, horn riffs and backing vocals that will open her heart and expose her soul.

Let her go.

And go she did.

Even though the sessions got off to a rocky start in Muscle Shoals (for a number of non-musical reasons that had nothing to do with Aretha), we were able to get that free-and-funky Muscle Shoals feel when I brought the Alabama boys up to New York to continue the recordings.

The first album, I Never Loved A Man (the Way I Love You), made history. The title tune was a smash. “Respect” turned into an anthem for the ages. “Dr. Feelgood” will never stop making us feel good. “Do Right Woman—Do Right Man” became a statement of eternal truth.

Before we knew it, Aretha was gracing the cover of Time magazine and being crowned the Queen of Soul. Her gospel-fueled power was being compared to Sam Cooke and Ray Charles. She had gone from a minor star on Columbia to a major star the world over. By the time the follow-up, Aretha Arrives, was released, they were clamoring for her in London, Paris and Tokyo. Her third album, Lady Soul, yielded no less than four hits: Don Covay’s rocking “Chain of Fools,” the Carole King/Gerry Goffin “You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” (with the title line by yours truly), and two brilliant Franklin compositions—Aretha’s “Since You Been Gone” and her sister Carolyn’s moving “Ain’t No Way.” (Incidentally, that was a title I suggested to Carolyn.)

Aretha’s talent as a writer emerged with the breakout smash from her fourth album, Aretha Now. I’m talking about “Think,” a song whose subtexts still resonate. In the middle of the turbulent sixties, when Aretha sang, “Think what you’re doing to me,” she was alluding to far more than the relationship between a man and a woman. Political relationships, racial relationships, economic relationships were all implicit. Before Marvin Gaye wrote What’s Going On and Curtis Mayfield penned Superfly, Aretha was infusing her music with messages that spoke to her people on many levels. Her consciousness was high.

It’s important to remember that, unlike today, these albums were cut in a hot New York minute. The four I’ve cited were all recorded and released within two years—and that’s not counting a fifth, Aretha in Paris. We were ripping and running like crazy.

At the same time, the studio vibe remained relaxed. As much as I’d like to take the bows for the priceless jewels we crafted, I can’t. My friends can testify that self-effacement is not my style. I live for approbation. But in the matter of making Aretha records—a matter that has great historical importance—I must be accurate.

Credit Aretha. In those days, artists rarely were called producers, even when they themselves served in that function.

Aretha was a true producer on all the records she made, but she’ll be the first to tell you that she was not alone. I suggested backing personnel. I suggested many songs. I suggested grooves. I certainly contributed ideas. Arif Mardin, consummate gentleman and inestimable arranger, was a major member of Team Aretha. Tommy Dowd, perhaps the finest engineer in the history of American popular music, contributed mightily in every way imaginable. The passing of those two friends in recent years, along with my partner Ahmet, is a continual source of bereavement.

Back in the sixties, though, it all came back to Aretha. It was all about bringing out Aretha; Aretha expressing Aretha; Aretha being Aretha.

Who was Aretha?

~~~~~

Aretha and I shared moments of tremendous mirth. She could be funny, whimsical, witty and playful. In the studio, she was absolutely delightful. There were occasional dinners and calls from home, but our relationship was mostly restricted to the studio. The studio was where we found musical joy.

We worked quickly. Aretha would find the tempo. She would give the Sweet Inspirations the notes to harmonize. She would sing down the lead and suggest a template for the horns. She would do all this sweetly, not aggressively. There were no arguments, no flare-ups, no confrontations. During the Golden Reign, the Queen was the model of decorum. We collaborated in the spirit of goodwill and creative excitement.

Back then the spirit was moving fast. It went like this:

Today Aretha’s in the studio to start a new album, Soul ‘69 or This Girl’s In Love With or Spirit in the Dark. Tomorrow’s she off to London or Miami. Next week she’s taping a TV special. Next month she’s singing at the Academy Awards. Meanwhile, she’s zooming up the charts. “I Say A Little Prayer” is a hit; “Call Me” is a hit; “Don’t Play That Song” is a hit; “Spanish Harlem” is a hit; “Rock Steady” and “Day Dreaming” and “Until You Come Back to Me (That’s What I’ll Do)” are monster hits.

We can’t miss. Or better yet, Aretha can’t miss. In the midst of this activity, it seems like everything we cut is striking gold.

~~~~~

Now comes this package that proves there’s more to Aretha than I ever knew about. Of course I knew that not everything we recorded had been released. What I didn’t know about the unreleased material, though, was how damn good it is!

We’ve discovered a treasure trove of vintage Aretha that’s nothing short of thrilling. Aretha’s outtakes are the sort of performances most artists would be proud to call first choices.

Before I walk you through these never-before-released tracks, I want to commend James Austin for spearheading this project and Patrick Milligan for doing the research that uncovered the jewels.

~~~~~

We open with three remarkable demos done in the winter of 1966: Aretha doing what would prove to be her break-out “I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Love You),” her “Dr. Feelgood,” another milestone in her career, and Van McCoy’s affecting “Sweet Bitter Love,” a song with great personal significance for Aretha. In fact, she felt “Sweet Bitter Love” so deeply that, although it never came out on Atlantic, she released two other versions: the first on Columbia in 1965 and the second, twenty years later, on Arista.

We start with these tracks, not only because the texture and tone of her voice marks the beginnings of her new artistic life, but because the demos themselves, stripped of all ornamentation, reveal the roots of Aretha’s Atlantic recordings: Aretha singing while playing the piano.

It’s a simple statement but a mighty concept. This is the foundation upon which everything is built. Strength emanates not only from the power of her magnificent voice but her fingers as well. Her chord constructions resonate with the sweetness of their sacred source.

Now to the matter of unreleased tracks:

“It Was You” and “The Letter,” taken at Sunday-go-to-church tempos that Aretha favored, has her moaning low, hungry for the love that has eluded her. Arif’s spare charts suit her admirably, allowing her to plead her especially poignant case.

“So Soon” was written by Van McCoy who, beyond his brilliant ballads, was adept with dance tempo material. Later he’d be immortalized for “The Hustle,” not to mention “Walk Away from Love,” the David Ruffin smash. The mood is whimsical, the groove smooth. Note the presence of sisters Erma and Carolyn. I always fantasized about an entire album of the Franklin Sisters. Here we get a glimpse of how memorable that record would be.

The sisters could sing and the sisters could also write. Carolyn’s great contribution would be the divine “Angel,” from the 1973 Quincy Jones-produced Aretha album. Back in the sixties, when Carolyn was still honing her skills, she wrote “Mr. Big,” her take on the neighborhood backdoor man (“a woman stealer… a rebel, a rooter, a bad motor scooter”). See Jean Knight’s huge hit, “Mr. Big Stuff,” cut three years later, for an apt archetypal analogy.

One of the beautiful things about Aretha is her sense of tradition. Raised in holy trinity of gospel, blues and jazz, she has knowledge and appreciation for all three genres. Because her life—and the life of her dad—is so central to that tradition, she has had personal contact with many of the greats. In 1968, when we were cutting Soul ’69, essentially a big band jazz album and an expansion of Aretha’s repertoire on Atlantic, she mentioned Little Willie John, her fellow Detroiter and an R&B giant. She wanted to record John’s signature “Talk To Me, Talk To Me” and did so with remarkable results. It’s all about that the deep-groove relaxation Aretha affects. I’m amazed that the track never made the record.

Aretha and the Beatles are an interesting story. Paul McCartney had sent me an acetate of “Let It Be” with a note that it was written for Aretha. We recorded it. Afterwards, though, Aretha told us to hold up the release. She liked the melody but wasn’t sure what the lyrics meant. Time passed and the boys from Liverpool were tired of waiting. They put me on legal notice that we no longer had the right of first release. They cut it themselves and, of course, enjoyed a huge hit. By 1970, Aretha saw the light and allowed us to include it, along with “Eleanor Rigby,” on This Girl’s In Love With You. Around that same time, we also cut Lennon/McCartney’s “Fool On the Hill.” The result is intriguing. It is, in the words of my colleague Patrick Milligan, “half Beatles, half Brasil ’66.” I always had my doubt giving Aretha material with ambiguous pop lyrics/ It was one thing when she sang “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” a storyline that’s straight church. But “The Weight,” a song she covered from the Band, was another matter. I’m not sure any of us understood the message. With “Fool,” though, the message is clear; Aretha tells the story with unambiguous conviction.

Johnny Ace, of course, is another iconic soul singer whose “Pledging My Love,” credited to promoter Don Robey, was already an R&B anthem when Aretha cut it in January, 1969. It became a B-side to “Share Your Love With Me” but appears here, in medley with “The Clock,” for the first time on album or CD. It is undoubtedly release-worthy, then, now and forever.

We New Yorkers were ever mindful of the soul stew brewing down in Memphis. So was Aretha. She adored the work of Isaac Hayes and David Porter. She took their “Taking Another Man’s Place,” first recorded by by Mable John, and brought it to another place entirely. In the storied tradition of Hayes/Porter’s “Your Good Thing (About to End),” also made famous by Mable John, “Taking Another Man’s Place” is one of those self-affirming female pronouncements that Aretha rendered so affirmatively.

We were at Criteria Studios in Miami when, in late 1969, Aretha cut three of the unreleased songs included here. The first, “You Keep Me Hanging On,” provides a telling comparison with Aretha’s fellow Detroiters and the gals who took the tune to number one three years earlier, the Supremes. Aretha admired Diana Ross and during her live act often did a loving impression of her (as well as Gladys Knight, Mavis Staples and Della Reese.) Aretha’s ability to the Aretha-ize the work of Motown maestros Holland-Dozier-Holland is a study in individual strength. The sheer force of her personality fortifies the song with a salty urgency that is all Aretha.

“Trying to Overcome” is another dynamic dirge. With its background echoes of (“You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” Aretha plays the part of the scorned female. “You make life bitter,” she sings, “sometimes you make it so doggone sweet…sometimes it’s hard for a woman to love a man.” One feels the autobiographical implications.

“My Way” goes the other way. It’s a heroic confirmation that, given its history in hands of Paul Anka and Frank Sinatra, would seem unsuitable for Aretha. No so. Aretha nails it. And in nailing it, she deconstructs, reconstructs and resurrects what many might consider cornball material. For me, this is one of the highpoints of the collection, a discovery of enormous value. Listening to it now, I forget about Paul and Frank and think only Aretha, Aretha, Aretha. She builds her case and claims the victory. The song becomes a royal pronouncement of incontestable truth. It’s a masterpiece.

Later that same year—1970—we were back in the Atlantic Studios in New York making more musical mischief:

I love the religious implications of the metaphorical “My Cup Runneth Over,” where once again Aretha bridges the gap between church and state. In her musical universe, it is all One Spirit.

“You’re All I Need to Get By” is an outtake of the song that was released on Aretha’s Greatest Hits in 1971. When we began considering this collection, I was against including alternate versions of previously issued material. My feeling was that pop songs, unlike jazz solos (say, by Monk, Bird or Trane), did not require such treatment. My colleagues convinced me otherwise. Or rather, listening to Aretha’s outtakes showed me the light. After a false start (where you hear me kibitzing a bit), Aretha launches into sometimes tentative but nonetheless stirring version of Ashford Simpson’s soaring anthem first captured by Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell. “You’re All I Need To Get By.”

“Lean On Me,” another song by Aretha favorite Van McCoy, was the B-side on “Spanish Harlem.” The production is big, brashy and churchy. Aretha’s on acoustic piano, and the rhythm section—get this—is Donny Hathaway, Cornell Dupree, Chucky Rainey and Bernard Purdie. Arif’s chart is perfection itself.

~~~~~

We begin with a marvel: the unedited and incomparable “Rock Steady,” Aretha’s own composition and surely one of her finest moments. “It was Donny Hathaway’s high organ lines,” she said later, “that kicked this thing off with such a funky flavor. I just love those lines.” I just love everything about this elongated version. (Chuck Rainey’s bass line always seemed to me a preview of hip hop.) Like the Mona Lisa’s smile, the beauty of its mystery remains. To reveal it to is betray it.

“Rock Steady” was part of Young, Gifted and Black, the album we cut during the winter of 1971. (On that same record, another fabulous Aretha composition, “Day Dreaming,” hit big.) We’ve discovered two songs from those sessions that were discarded, overlooked or both. They’re both solid. The presence of my dream rhythm section—Dupree, Rainey, Purdie and Aretha on piano—keeps the rocking steady and strong. “I Need A Strong Man” is another chapter in the search for a righteous man while “Heavenly Father” beseeches God to protect that the man who mercifully has been found. When

Aretha slips into prayer mode, by the way, even I, a crotchety old atheist, must bow before the higher power.

Aretha did, in fact, return to church to record Amazing Grace with James Cleveland in Los Angeles, an album considered a gospel classic. Following that unqualified success, she asked if I would object to having Quincy Jones produce her next record. I was delighted. I’d known and worked with Quincy since the fifties. Q spoke of taking Aretha in a jazz direction. Nothing would please me more.

The only thing that didn’t please me was the fact that record took well over a year to make—and this during an era when it wasn’t unusual to turn out an album in three weeks. But the outtakes included here show that there was a great deal of creative experimentation going on.

My favorite is “After Hours,” Aretha’s stretched-out nine-minute meditation on the Erskine Hawkins standard. This has been required repertoire for every blues/jazz keyboardist since it was recorded by Avery Parish in 1940. Aretha’s considerable piano chops are on display, but it’s her go-tell-on-the-mountain blues vocal that gives me goose bumps and places her in that elite venue where the eternal masters like Ma Rainey and Big Joe Turner Joe live.

The overall quality of the cuts that never made the Quincy/Aretha album Hey Now Hey (The Other Side of the Sky), finally released in 1972, is extraordinarily high. “Tree of Life,” that begins, of all things, with a quote from the famous Joyce Kilmer poems, turns deep, exploring roots that are both complex musically and theologically. The song turns into a sermon on the last days. “Do You Know” is a get-down low-down secular sermon. “I’m a girl of a few words,” says Sister Re, “but I’ve got something to say.” “Can You Love Again” has a lovely country feel while “I Want To Be With You” is one of those touching love songs, sung out of rhythm with such ringing sincerity that you find yourself listening to it over and again. The final Aretha/Quincy cut, an alternate of Bobby Womack’s “That’s The Way I Feel About You,” easily rivals the released version.

A special treat is the inclusion of Aretha’s duet with Ray Charles from a Duke Ellington TV tribute that Quincy produced in 1973. We all remember Ray’s impromptu appearance on Aretha’s Live at Fillmore West when they sang “Spirit in the Dark.” This time they revisit the experience through an Ellingtonian lens, turning the wordly text into sacred wisdom. As Aretha once said about her pairing with Ray, “It’s soul overload, but give me more of where that comes from.”

Let Me In Your Life, With Everything I Feel in Me and You were the last three albums I produced for Aretha. They were released in 1974-5 and marked the end of our working relationship. Combing through the vaults we found three remarkable unreleased items from Let Me In Your Life. The first, the paradoxically titled “Happy Blues,” is defiantly upbeat and an affirmation of Aretha’s tenacious spirit. “At Last,” of course, is the Harry Warren standard, first recorded in 1941 but immortalized by the great Etta James in 1963. Aretha’s reading is incomparable and has me scratching my head and wondering why in hell didn’t we release it? The same must be said for “Love Letters,” the Edward Heyman/Victor Young gem that Nat Cole defined for all times in his landmark 1956 Love is the Thing album. Or so we thought. Aretha revisits the song and, in doing so, reminds that, like Cole and Sinatra, she instinctively knows the difference between sentimentality and sensitivity. Finally, we couldn’t resist an alternate version of Womack’s “I’m In Love” wherein Aretha soars to the heavens.

~~~~~

The set concludes on a bittersweet note.

We end, in fact, where we began, with an unadorned demo: Aretha and piano. As I head towards my 91st birthday and think back to those glory days, a song entitled “Are You Leaving Me” resonates with special poignancy. Those days are indeed gone. At the end of the seventies, Aretha left Atlantic for “greener pastures” at Arista where her fabulous career got even more fabulous. My life as a producer went on. Fortunately I found favor with other wonderful artists.

But there could never be another Aretha. Aretha changed it all for me. Working with her was the gift of a lifetime.

Her work, of course, expanded as she collaborated with grand producers like Curtis Mayfield, Luther Vandross, Narada Michael Walden and Lauryn Hill. In recent years there have been beautiful recordings and priceless moments. The way she rose to the challenge of substituting for Luciano Pavarotti at the Grammys was inspiring. Up there in opera heaven, Puccini had to be smiling.

Eastern philosophies instruct us to live in the present. Amen. I’m there. At the same time, our present minds are built on memories. And when the memories are as overwhelmingly beautiful as the music on these discs, my spirit is enriched.

Aretha Franklin is an artist who enriches our lives.

I’m grateful to her.

We all are.

Jerry Wexler, a former partner in Atlantic Records, is enshrined in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. There’s talk of Mount Rushmore.

David Ritz has co-authored many books, including the autobiographies of Jerry Wexler and Aretha Franklin.